Nāgārjuna (ca. 150 – ca. 250 CE)

Nāgārjuna (ca. 150 – ca. 250 CE)

Widely regarded as one of the most important Buddhist philosophers and, along with his disciple Āryadeva, as the founder of the Madhyamaka school of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Nāgārjuna is also credited with developing the philosophy of the Prajñāpāramitā sūtras and, according to some sources, with having revealed these scriptures in the world after having recovered them from the world of the nāgas (water spirits often depicted in the form of serpent-like humans). Very little is reliably known of his life, since surviving accounts were written in Chinese and Tibetan centuries after his death. According to some accounts, he was originally from South India. Some scholars believe that Nāgārjuna was an advisor to a king of the Satavahana dynasty. Archaeological evidence at Amarāvatī indicates that if this is true, the king may have been Yajña Śrī Śātakarṇi, who ruled between 167 and 196 CE. On the basis of this association, Nāgārjuna is conventionally placed at around 150–250 CE. According to a 4th/5th-century CE biography translated by Kumārajīva, Nāgārjuna was born into a Brahmin family in Vidarbha, a region of Maharashtra, and later became a Buddhist. The Mūlamadhyamakakārikā is Nāgārjuna's best-known work. Nāgārjuna's major thematic focus in this text is the concept of śūnyatā, translated into English as "emptiness", which brings together other key Buddhist doctrines, particularly anātman, or "not-self," and pratītyasamutpāda, "dependent origination", to refute the metaphysics of some of his contemporaries. For Nāgārjuna, as for the Buddha in the early texts, it is not merely sentient beings that are "selfless" or non-substantial; all phenomena (dhammas) are without any svabhāva, literally "own-being", "self-nature", or "inherent existence" and thus without any underlying essence. They are empty of being independently existent; thus the heterodox theories of svabhāva circulating at the time were refuted on the basis of the doctrines of early Buddhism. This is so because all things arise always dependently: not by their own power, but by depending on conditions leading to their coming into existence, as opposed to being. Nāgārjuna means by real any entity which has a nature of its own (svabhāva), which is not produced by causes (akrtaka), which is not dependent on anything else (paratra nirapeksha). Chapter 24, verse 14 of the Mūlamadhyamakakārikā provides one of Nāgārjuna's most famous quotations on emptiness and co-arising:

sarvaṃ ca yujyate tasya śūnyatā yasya yujyate

sarvaṃ na yujyate tasya śūnyaṃ yasya na yujyate

All is possible when emptiness is possible.

Nothing is possible when emptiness is impossible.

Text source: Wikipedia (edited). This version of Wikipedia content is published here under a

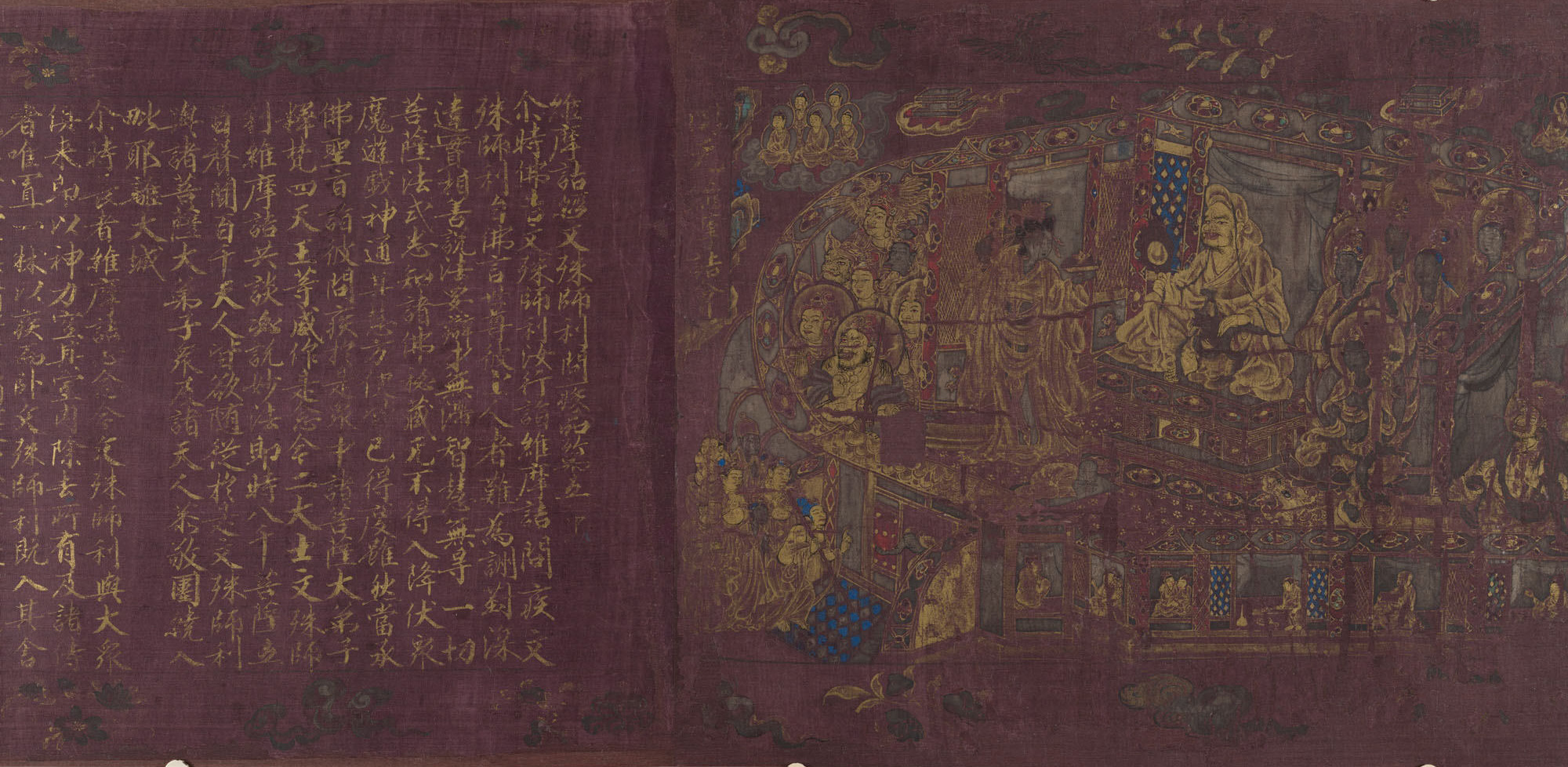

Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Left: A Tibetan distemper painting depicts Nāgārjuna (l) and Aryadeva (r) sitting on a floating platform; Nāgārjuna receives a book from a

nāga (mythic serpent) emerging from the water.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons. Image author: Unknown.

Image license: Public domain. All books in the gallery immediately below are by Nāgārjuna unless otherwise noted.

Aśvaghosa (ca. 80 – ca. 150 CE)

Aśvaghosa (ca. 80 – ca. 150 CE) Nāgārjuna (ca. 150 – ca. 250 CE)

Nāgārjuna (ca. 150 – ca. 250 CE)

Asanga (4th c. CE)

Vasubandhu (4th – 5th c. CE)

Dharmakīrti (6th or 7th c. CE)

Dharmakīrti (6th or 7th c. CE) Śāntideva (8th c. CE)

Śāntideva (8th c. CE)